by Carl Strang

My other presentation at Saturday’s Wild Things conference reviewed the range extensions by 8 species of singing insects that have turned up in our region in recent years. I ran through them in the chronological order of their discovery, and then offered some general points.

Broad-winged tree cricket (Oecanthus latipennis)

Map from the Singing Insects of North America website (SINA), 2012. The record in DuPage County resulted from this study, and was added in 2006. Prior to that the species was not supposed to occur in the Chicago region.

Original range sources: Hebard 1934 (“Northern limits of distribution are Hilliary and Quincy”), McCafferty & Stein 1976 described it as a central and southern species in Indiana, with Tippecanoe County the northern extent. I found them in DuPage County in 2006, and subsequently learned they are abundant throughout the county. They also have reached the junction of the Wisconsin and Mississippi Rivers in Wisconsin.

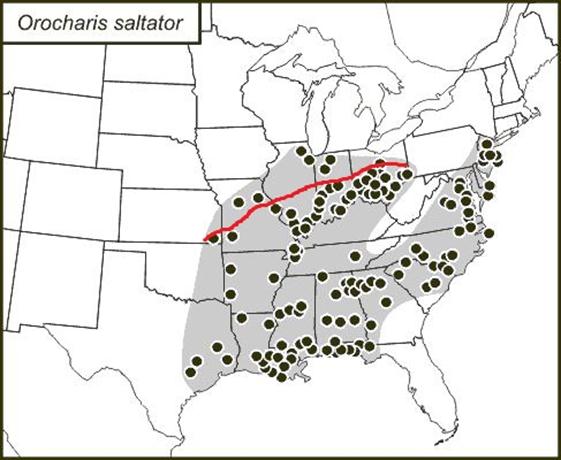

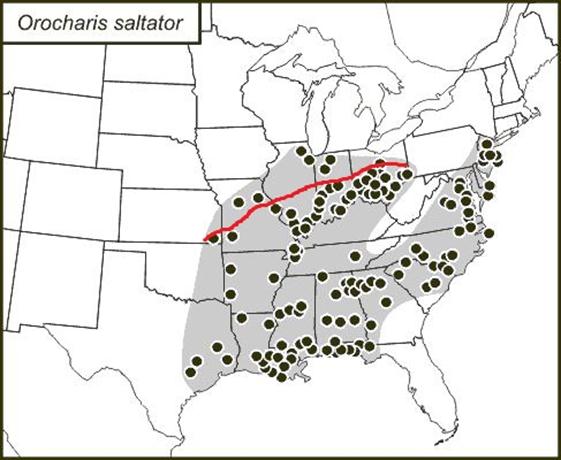

Jumping bush cricket (Orocharis saltator)

Jumping bush cricket SINA map, 2012. The added red line indicates the northern range limit as of 1969, when Tom Walker reviewed the genus.

Original range sources: Hebard 1934 (Shawneetown northern limit in Illinois; “should however be found throughout southern Illinois as it is known as far north as central Indiana”). McCafferty & Stein 1976 (“known only from the southern two-thirds of the state” with Tippecanoe County given as the northern limit). They are rapidly expanding in DuPage County, abundant in the southern half and spreading into the northern half with new northern limits found annually. I also have heard them at Indiana Dunes State Park.

Roesel’s katydid (Metrioptera roesellii)

Roesel’s katydid SINA map, 2012. Prior to work by Scott Namestnik and me, the range was thought to end in northeastern Ohio, with a small disjunct area in northeast Illinois. The red dots indicate our added findings in 2012.

Original range sources: Roesel’s katydid is a European species that in North America first was found in two suburbs of Montreal, Quebec (Urquhart and Beaudry 1953, Beaudry 1955), and is thought to have been introduced between 1945 and 1951. Vickery (1965), who summarized this history, reported that the species had spread into New York state and Vermont by 1965, and that the long-winged variants that originally had dominated the Montreal population were diminishing in favor of the short-winged forms typical of the European continent. The Montreal population apparently was by then limited by an indigenous parasitic nematode. Roesel’s reached Ithaca, NY, by 1965 (G.K. Morris, as reported by Shapiro 1995), and Long Island by 1990 (Shapiro 1995). Short-winged forms were dominating the St. John, New Brunswick, population by 2008 (McAlpine 2009), and so had arrived some unknown number of years earlier. Nickle (1984) reported finding them in Pennsylvania by the early 1980’s. Roesel’s katydids were collected in two northeastern Illinois counties in the late 1990’s (Eades and Otte, no date). I found them in north central Indiana in 2007, and subsequently Scott Namestnik and I have found them throughout northern Indiana (as far south as Indianapolis) northeast Illinois, and last year the Lower Peninsula of Michigan. Others have added Ohio, Wisconsin and eastern Iowa.

Round-tipped conehead (N. retusus)

Round-tipped conehead SINA map, 2012. The added red line indicates the northern extent of the range in Illinois in 1934 and in Indiana in 1976.

Original range sources: Hebard 1934 (“Urbana is a northern limital point”), and McCafferty and Stein (1976) had none north of Indianapolis, but they are so common in northwest Indiana and northeast Illinois now that this is a well advanced range expansion in the intervening decades. I also heard a single singing individual in a meadow at Wyalusing State Park in Wisconsin in 2007.

Handsome trig (Phyllopalpus pulchellus)

Handsome trig SINA map, 2012. The northern dot at St. Joseph County, Indiana, is the result of Scott Namestnik’s work.

Original range sources: Hebard 1934 (northern limits given as Marion County in Indiana and Monticello in Illinois; “confined to southern and central Illinois”). McCafferty & Stein 1976 indicated a northern extent in Tippecanoe County. In 2009 Scott Namestnik was posting photos of them from St. Joseph County.

Swamp cicada (Tibicen tibicen)

Original range sources: This species was mentioned by Alexander, Pace and Otte in their (1972) Michigan singing insects paper, but they expressed doubt that it was a breeding species in the state. However, a later paper (Marshall, Cooley, Alexander and Moore 1996) reported finding it in extreme southern MI (intensive searching found it only in the southern portions only of the southern tier of counties. They were not willing to say whether this represented a range extension or the species being missed earlier). I first found it in Marshall County, Indiana, and DuPage County, Illinois, in 2010, but suspected I had heard it earlier. They are scattered across the southern half of DuPage.

Slightly musical conehead (N. exiliscanorus)

Slightly musical conehead SINA map. This does not yet reflect our finding them in Porter and Marshall Counties, Indiana, in 2012.

Original range sources: Hebard 1934 (northern limits indicated as Tower Hill in south central Illinois, and New Harmony in Indiana). McCafferty & Stein 1976 (“In Indiana it is known only from heavy thickets and grasses along the Ohio River”). Gideon Ney, Nathan Harness and I, seeking slender coneheads, found this species at the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore in 2012, and I found it in Marshall County as well.

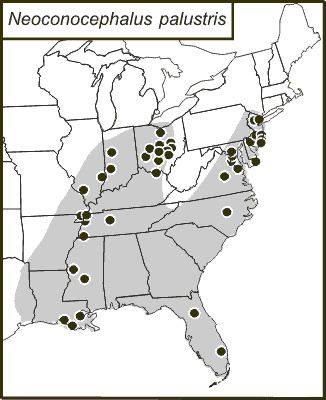

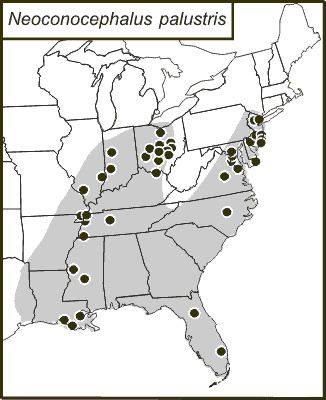

Marsh conehead (N. palustris)

Marsh conehead SINA map. This does not yet reflect our finding them in Porter County, Indiana, in 2012.

Original range sources: Hebard 1934 (“Lawrenceville and Carbondale are northern and western limits respectively for palustris…It is probably confined to the southern portions of Indiana and Illinois.”). McCafferty & Stein 1976 reported Tippecanoe County as the northern known extent. Ney, Harness and I found this species to be common at Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore and present in the state park.

General Points

Most of these range extensions are from south to north. Exceptions are Roesel’s katydid (east to west) and the broad-winged tree cricket (spreading south as well, according to SINA coordinator Tom Walker).

I do not know whether any other of these species likewise are spreading south or in other directions.

Some of these are clear range expansions, as they are species which were well known at the time of earlier studies, and now have become abundant beyond the range as then drawn: broad-winged tree cricket, jumping bush cricket, Roesel’s katydid, and round-tipped conehead.

The others have a spottier distribution, or may not have been as well known then, and so might have been missed by earlier researchers: handsome trig, swamp cicada, slightly musical conehead, and marsh conehead.

As for the possible connection between these range extensions and climate change, Gonzalez (2012) mentioned a calculation, based on work in Gonzalez et al. (2010), indicating that the region’s climate has undergone a temperature change equivalent to a southward shift in latitude of 100km in the 20th century. This is consistent with the magnitude of many of these observed range changes.